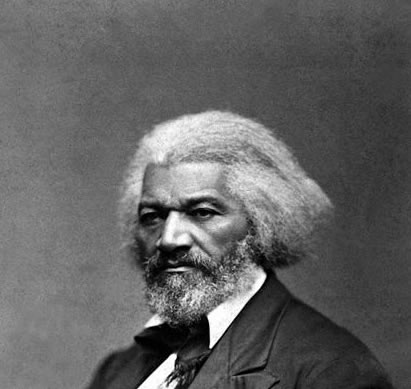

Frederick Douglass |

Frederick Douglass Life Timeline – This chart requires students to research Frederick Douglass on mrnussbaum.com before filing out a chart that describes the major milestones and accomplishments of his life Douglass was soon sent away to another slave owner named Mr. Freeman. Mr. Freeman allowed Frederick to teach other slaves to read. Frederick taught over 40 slaves how to read passages from the New Testament. Other slave owners, however, became angry and destroyed the “congregation” in which Frederick taught. Four years later, in 1837, Frederick married a free black woman named Anne Murray. They would have five children. He gained his own freedom by escaping from captivity by dressing as a sailor and boarding a train at Havre de Grace, Maryland, near Baltimore. By the time he reached New York City he was a free man (though not officially a free man). The trip took less than a day. Douglass continued to Massachusetts and soon joined the abolitionist cause. Inspired by the famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass became an anti-slavery speaker and writer. At only 23 years of age, Douglass became a leading speaker for the cause and joined several movements including the American Anti-Slavery Society. He also supported the feminist cause and participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, a women’s rights convention in 1848. In 1845, Douglass authored Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, an autobiography. The book was a critical success and became an instant best seller. The book was translated into three languages, and Douglass was invited to tour Ireland and Great Britain. Douglass spent two years in Europe lecturing on the horrors of slavery. Douglass became a popular figure in Great Britain, where his lectures were “standing room only.” The people of Great Britain, roused by Douglass’s speeches, raised money on his behalf to pay his “owner,” Hugh Auld, for his official freedom. Auld was paid 700 pounds by the people of Great Britain and Douglass was officially a free man in America. When he returned to America, Douglass published The North Star and four other abolitionist newspapers under the motto “Right is of no Sex — Truth is of no Color — God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.” He advocated equal education for black children, who received virtually no funding for education. As his reputation grew, Douglass became an advisor to Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. Douglass led a growing movement that caused a split in the Abolitionist movement. Douglass and others believed the US Constitution was an anti-slavery document, while William Lloyd Garrison believed it was a pro-slavery document. In addition, Garrison believed that The North Star was competing for readers with his own newspaper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. By the time of the start of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the nation’s most prominent black men. Later, The North Star was merged with other newspapers and was called the Frederick Douglass Paper. Douglass believed the primary cause of the Civil War was to liberate the slaves. After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass continued in the fight for the rights of the freed slaves. After the assassination of President Lincoln, Douglass gave an impromptu speech at his memorial service. While Douglass’s speech mentioned Lincoln’s shortcomings in the fight against slavery, he gave Lincoln much credit for the liberation of the slaves, “Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?” The speech was followed by a rousing standing ovation. It is said that Mary Lincoln was so moved by the speech that she gave Douglass Lincoln’s favorite walking stick. After the war, Douglass was made president of the Freedmen’s Bureau Savings Bank and several other diplomatic positions. During reconstruction, Douglass frequently gave speaking tours, particularly at colleges and universities in New England. In 1877, he purchased his final home, which he named Cedar Hill, in the Anacostia section of Washington, DC. Today, the estate is known as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. Frederick’s wife, Anne Murray, died in 1881, but he remarried Helen Pitts, a white abolitionist, in 1884. Despite the controversy that their marriage created (she was white and twenty years younger than he), the pair toured Europe in 1886 and 1887. In 1895, Douglass died of a heart attack at his home in Washington. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| John Bell Hood | |||

|

|

|

|

| Joseph Johnston | |||

|

|

|

|

| William H. Seward | Edwin M Stanton | ||

|

|

|

|